Colorado native Roland Green was an English literature major at Western Colorado University who dabbled in poetry writing and spent countless, blissful hours skiing the Rocky Mountain slopes.

Ever a history buff, when the Berlin Wall fell, Green was curious to find out what had become of the Eastern European countries finally free from Russia’s chains. “This is history,” he said. “I wanted to see it, not just read about it.”

Green dropped out of college and wound up in Prague, teaching English at a university, and learning from his students about life under Communist rule.

“I figured it was time to do something meaningful. Maybe I could bring the forests back to life,” Green said.

So he returned to the U.S., earned a degree in biology from Colorado State University and came to UW-Madison for its environmental toxicology graduate program.

Today, Green is focused on a different type of toxins, those found in the human body: cancerous tumors.

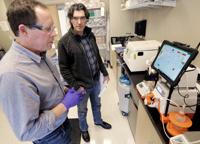

Green, 53, is CEO and co-founder of Invenra, a Madison company working on drugs to fight cancer, a company so promising it has forged collaborations with two successful drug companies even though it doesn’t have a single drug in human trials yet.

One of the agreements could eventually bring Invenra $1.4 billion — if all goes well.

“Everyone calls those numbers ‘biobucks,’” Green said. Usually, the payments don’t reach those levels, he said, and even if they do, that’s “way off in the future.”

Invenra’s technology, though, is a fairly hot commodity in the drug development world right now.

And the company is growing. Investors just poured another $7 million into Invenra’s coffers, which will finance a larger staff.

At 28 employees — up by 10 in the past six months — Invenra plans to move from 505 S. Rosa Road to larger quarters in University Research Park next year. Green said the staff could reach 50 by the end of 2019. The new facilities will have room for up to 80 employees, he said.

“We’re hiring steadily — pretty much as fast as we can find good people,” said Green, whose jeans, collar-length hair and laid-back manner may more likely reflect his outdoorsy side than his role as leader of an ambitious drug discovery company.

Aaron Olver, managing director of University Research Park, said he is glad to see Invenra getting recognition.

“Our board recently received a briefing from Invenra and was blown away by its potential to save lives,” Olver said.

Two-armed antibodies

Invenra’s novel technology is based on bispecific antibodies that latch onto two targets, giving cancer a double-punch.

Antibodies are blood proteins produced to fight off bacteria and viruses that invade the body. They are y-shaped molecules with two arms.

Invenra produces antibodies in flasks in the lab and then screens them to see if they bind to cells of the targeted disease or to a patient’s immune cells so the body’s immune system will fight off the disease, a process called immunotherapy.

“Our focus is modulating the patient’s immune system to try to get it to attack the cancer,” Green said.

While most antibody treatments up to now have aimed at only one target, bispecifics employ both of the molecule’s arms to bind to two targets. Often, one arm links to a T-cell — a white blood cell sent by the immune system — and the other arm hits on the cancer cell.

“There are a lot of things you can do with two hands instead of one,” Green said.

More than 60 active or completed clinical trials using bispecific antibodies are listed on the U.S. National Library of Medicine’s website clinicaltrials.gov. So far, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved one bispecific produced by Amgen to fight a form of leukemia.

Invenra calls its production process the B-Body platform, and it has developed three types of bispecific antibodies: T-cell engager, Sniper, and Archer.

- T-cell engagers grab a patient’s T-cells and bind them to cancer cells, causing the T-cells to kill the cancer cells.

- Snipers are second-generation molecules that can distinguish between cancer cells and healthy cells better than regular antibodies. They seek out a combination of two separate targets on a cancer cell that are not found on healthy cells and flag them for destruction. They can also be used to carry a toxic payload to the cancer cells.

- Archers can dial up a T-cell’s activity.

Invenra is preparing for the first tests of its bispecific drug candidate OX40 in mice. OX40, an Archer, is designed to “hit the gas pedal on T-cells,” Green said. “We think it has a much better chance of making a difference for patients.” Invenra hasn’t determined yet which cancer it will target with OX40.

It will probably be 2020 before any of the company’s drugs are tested in humans, Green said.

Progress through partnerships

Invenra’s platform is intriguing enough that Exelixis, a publicly traded California drug development company, signed a contract last May to get an exclusive, worldwide license for one unnamed Invenra drug compound — a T-cell engager — and to work on up to six more drug prospects together.

Under the agreement, Invenra will receive a $2 million payment as each project begins. Terms spelled out for the first drug say Invenra will be eligible to get up to $131.5 million in milestone payments as the drug goes through the testing process and up to $325 million more if the drug is approved, goes to market and meets certain sales goals.

That totals a potential $458.5 million for the first drug alone, not counting royalties, if all goes well.

According to documents Exelixis filed with federal regulators, the two companies already are jointly developing two drug prospects, and Exelixis had paid Invenra $4 million by June 30.

“That’s real money for us, and it goes a long way for us here in the Midwest,” Green said.

He said he thinks Invenra can provide Exelixis with several strong contenders within about three years, and it could take seven to 10 years to get each one through the regulatory process.

Exelixis hopes to get three drugs on the market as a result of the collaboration, he said. If that happens, and sales are strong, the arrangement could be worth nearly $1.4 billion plus royalties for Invenra.

But that’s not the Madison company’s only iron in the fire.

Invenra also has active collaborations with drug giant Merck; QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute in Australia; and AgonOx, a Portland biotechnology company, to develop pharmaceuticals. Those relationships are bringing money to Invenra, as well, but Green said he can’t disclose how much because of confidentiality agreements.

“Biologics are now playing a key role in treatment of cancer and other diseases, and Invenra is poised for major growth through these types of partnerships,” said Lisa Johnson, CEO of BioForward Wisconsin, the nonprofit that promotes the state’s biohealth industry.

Invenra is developing drugs on its own, too. A project with UW Health pediatric oncologist Dr. Paul Sondel aims to create a drug to treat children with neuroblastoma, a rare form of childhood cancer that often starts in the adrenal glands above the kidneys.

The current, commonly prescribed treatment strikes nerve cells as well as cancer cells, causing severe pain, Green said. “Kids have to take intravenous morphine to tolerate the drug,” he said.

He said Invenra’s drug prospect, a Sniper, is less painful. “Our antibody will fall off the nerve cell but will stick to the target on the cancer cell,” he said.

Green said if the project works successfully to treat neuroblastoma, it could work for other cancers, too, such as glioblastoma (a form of brain cancer) and small cell lung cancer.

“We’re very excited about that project,” he said.

Wisconsin investors

The $7 million raised in October includes new backers — Madison-base Venture Investors and the State of Wisconsin Investment Board. Wisconsin Investment Partners, an organized group of individual investors, added to its previous funding for Invenra.

Founded in 2011 by Green and Emile Nuwaysir — both of whom had been co-founders of NimbleGen, a Madison company whose technology for rapid DNA and RNA analysis was sold to Roche in 2007 for $272.5 million — Invenra has now raised $22.5 million.

Green said it’s “an exciting time” to be in the biopharmaceutical field.

Invenra’s partnership with companies such as Exelixis, which already has three drugs on the market, and drug giant Merck benefit the entire area, said Tom Still, president of the nonprofit Wisconsin Technology Council.

“It underscores the fact that Madison and Wisconsin are building a cluster around cancer treatment. Plus, it provides yet another link between the Madison area and major technology companies on the West Coast,” Still said.

The father of two college-age children with his wife, Elizabeth, and an avid rock-climber, Green said thinking about how Invenra’s products could eventually help patients keeps him “motivated to go to work.

“There’s still a part of me that wants to be out hiking and skiing,” he admitted. “Now, it’s time to give back.”

Creating cancer-fighting drugs is “kind of far from saving the forest,” Green said. “But I may circle back to that someday.”

Recent Comments